November 2, 2022

Following Five Steps to Safer Elections to Build a Security Partnership in Utah

The case study is available for download:

A Weber County Conference Provides a Model

A series of threatening incidents in 2022 raised concern for the safety of election administrators in Utah. Vitriolic voicemails included one from a man who stormed out of an explanatory session making threats if his demands for procedural changes were not met, while another man threatened “revolt, maybe with violence.” Activists who want to replace ballot-counting machines with hand counts were promoting their agenda by organizing an “armed march.”

“They used to think we were naive, victims, but now they’re starting to say we’re corrupt,” said one seasoned election official, describing the changing threat environment. Violence inspired by election misinformation no longer seemed unthinkable in Utah.

News of such threats had not spread widely outside circles of election administrators, neither to the public nor among law enforcement. Violent rage about a “dishonest count” is not intuitive in a state where the contest for president was decided by a 20% margin. As in most states, previous elections required little law enforcement beyond settling minor disputes over concerns of electioneering; sign placement or passing out leaflets near voting locations. Local law enforcement had not prepared for major disruption at voting locations or aggression aimed at election workers.

The Solution

Reaching cross-institutional consensus on the severity of the threat can set the stage for a new protective posture. Security strategies will need to be attuned to election rules and procedures as well as constitutional rights to speech, to assemble, to bear arms and – not least of all – to vote.

The northern Utah experience shows that when election officials take the lead and law enforcement is open to cooperation, they can work together to grapple with the unique needs of the election environment.

Using the resources created by the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections (CSSE), Weber County Clerk/Auditor Ricky Hatch recruited Weber County Sheriff Ryan Arbon as a law enforcement partner. The two officials believed a multi-county meeting could unite leaders around a consensus on security needs. Arbon agreed to corral law enforcement leaders, while Hatch took the lead in the election community. They scheduled their meeting immediately after an existing gathering of police chiefs to facilitate their attendance.

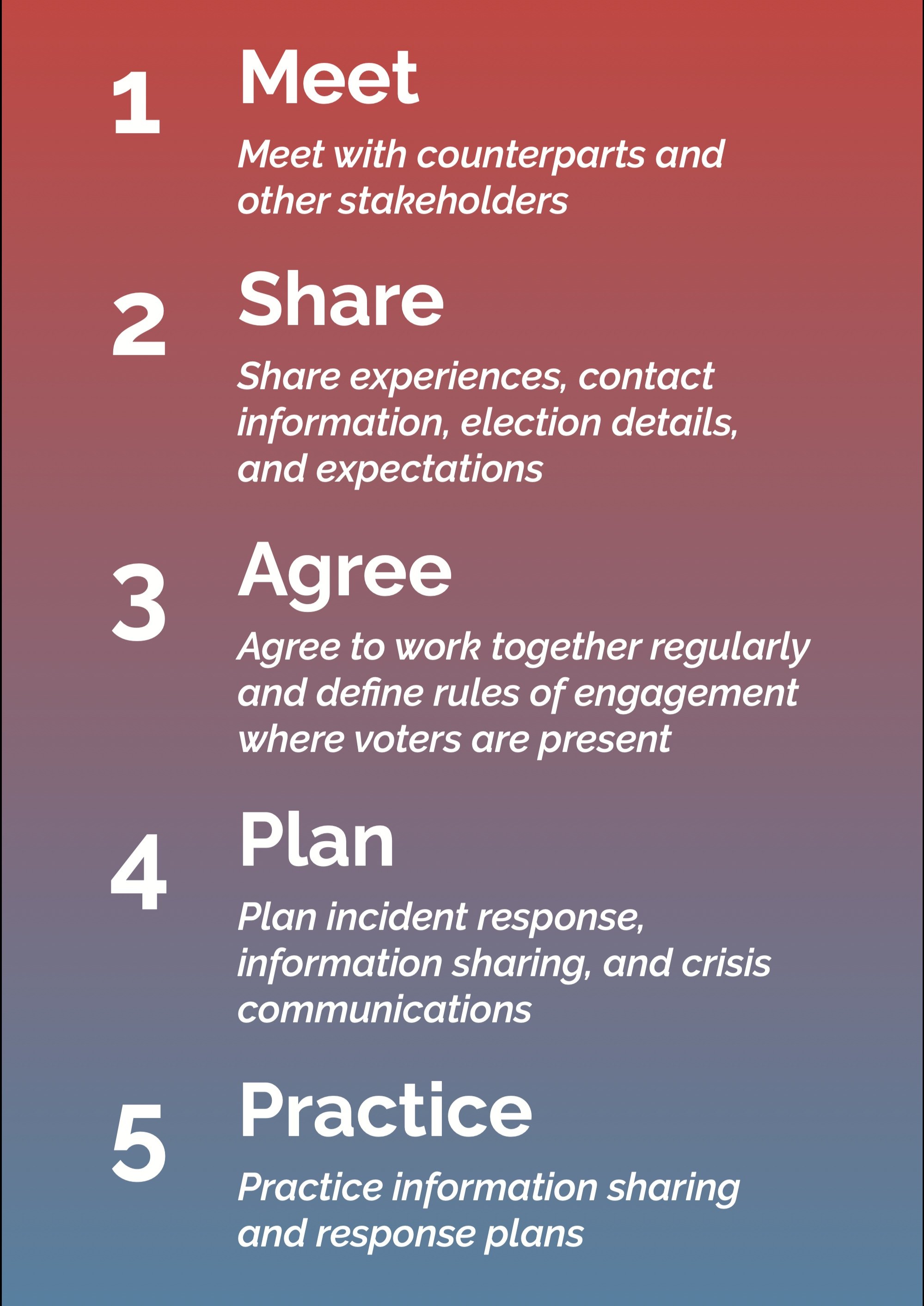

Hatch’s agenda relied on the Five Steps to Safer Elections, a guide published by CSSE. By providing a roadmap for cooperation, the guide gave Hatch, a CSSE member, confidence the meeting could succeed in building consensus.

Speakers represented key institutional constituencies, each addressing critical topics and expressing key tenets of Hatch’s vision. To set a tone of professionalism while underlining critical issues, he drew on CSSE-provided resources including a law enforcement election safety training video and a “challenge coin,” a token expressing a shared commitment to safety in elections.

The northern Utah experience shows that such a meeting can inspire a new security posture. Participants from the elections community cited two key outcomes: meeting law enforcement face to face to open lines of communication and thinking through scenarios they had only considered in general terms. Law enforcement attendees stressed learning about election law and beginning to think about unique aspects of the election legal environment.

The Northern Utah Model for Election Security Cooperation

Hatch used the Five Steps to Safer Elections guide as his roadmap. The guide points to these key mileposts on the road to security cooperation:

-

Meeting to open lines of communication

-

Sharing stories and details that create a mutual understanding of the need and how to address it

-

Agreeing on routine security support and basic rules of engagement

-

Planning in detail how to address more threatening scenarios, and

-

Practicing the response, because such situations may be infrequent, but they will require finesse and adherence to the plan should they arise.

The northern Utah meeting focused on the first three steps – meeting and sharing the background to create a basis for agreement on the general outlines of a security response.

A Meeting to Open Lines of Communication

“Awareness is security” is how Tina Barton, a CSSE member and former Michigan election official, describes the importance of simply pulling law enforcement and election officials into the same room. So many election administrators have fielded threats that it is a common topic at state and regional election conferences. But many members of the law enforcement community are not aware of the intensity of the threat.

Reaching law enforcement with his message was Hatch’s top priority. He started with Arbon, who was the Utah Sheriffs’ Association’s 2021 Lawman of the Year and a trusted colleague. With a background as a city police chief in a neighboring county, Arbon’s reputation and deep connections were assets.

Hatch asked Arbon if he could speak briefly to an existing meeting of Weber County police chiefs, but their conception quickly expanded. The two instead decided to schedule a separate election security meeting immediately afterward, believing the convenience would ensure many chiefs stayed.

Arbon felt Hatch’s prominence in the state as former president of the Utah Association of Counties and a regular witness to legislative committees would draw law enforcement. Rather than writing his own, he forwarded the invite from Hatch to carry the weight of both names.

For his part, Hatch invited election officials from neighboring counties and representatives from the Utah Lt. Governor’s office (the state’s chief election official) and the Utah Association of Counties.

Planning the Meeting – Agenda and Speakers

Planning meetings with law enforcement representatives – Arbon and Weber County Attorney Chris Allred, the local prosecutor – helped refine the agenda and reinforce the growing relationship between elections and law enforcement in Weber County. Starting from a list of topics drawn from the Five Steps to Safer Elections, they adjusted priorities based on their perceptions of northern Utah’s needs and sensibilities:

-

Establishing the need for security support

-

Understanding each other’s operating environment

-

Agreeing on expectations and limitations to security support

They recruited speakers to address those priorities, asking representatives of law enforcement and elections to speak at each stage and anchoring key groups of stakeholders by putting someone representing them at the podium. The final list included a sheriff, a clerk, representatives from a county attorney’s office and the Utah state elections director, as well as national figures from the election safety field.

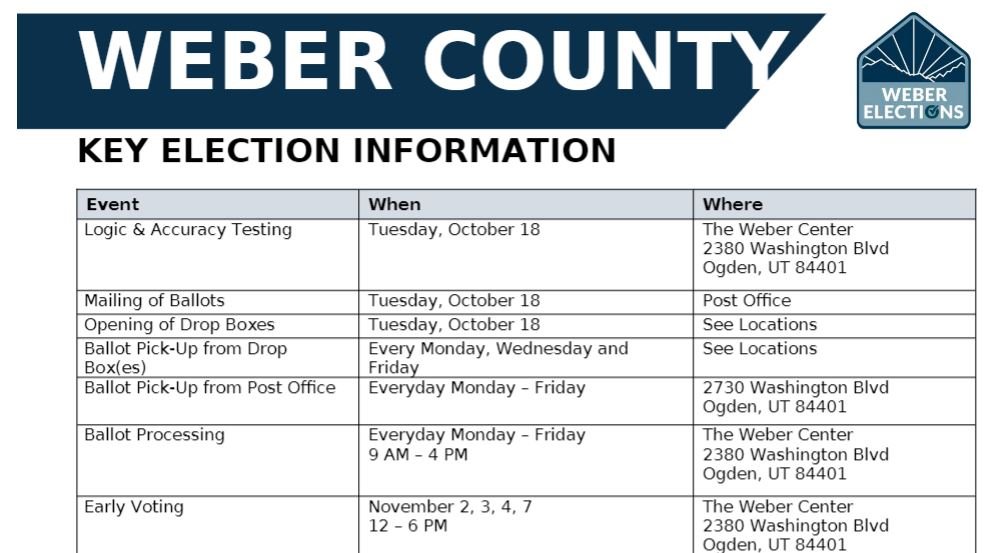

Hatch consulted with members of CSSE before distributing new resources to participants including a Utah election law pocket guide and an election information template to provide law enforcement with key dates and contacts in the election office and at voting sites.

As the meeting approached, Hatch expressed confidence the agenda set the right priorities and the speakers chosen and the resources brought to the table would reinforce each important message.

Establishing the Need for Security Support

Although ongoing election security challenges appear in national news, some police chiefs, sheriffs and election administrators may not recognize the degree of danger for election officials and its expanding impact even in places like northern Utah where partisan majorities are strong and stable. Police are also managing similar upticks in incidents in school and healthcare environments. A security meeting must convince participants that election security is an urgent responsibility.

To make the case, organizers invited CSSE members Tina Barton and Harold Love. Inviting out-of-state figures underscored the national importance of election safety, lending both gravity and practical experience, Hatch said.

Barton, who served as the Rochester Hills, Michigan, clerk for nearly 10 years, shared dramatic audio of threatening messages she received after a minor mistake in her office. She identified and immediately corrected the mistake, but she and her office briefly became a focal point of conspiracy.

When Barton played the clip, the rapid-fire stream of vulgarity and violence provoked nervous laughter and embarrassed sidelong glances from attendees, surprised at the over-the-top ugliness and menace. She hammered home the point for the largely male audience by asking them to take a moment to imagine their own wives, mothers or daughters answering such a phone call.

“I’m trained to make sure everyone can vote, and you’re trained to keep me safe,” Barton said, underlining the need for security support by contrasting the perspectives of law enforcement and election staff. “We need your help.”

Love, a retired police captain from Michigan, appealed to the officer’s oath to serve and protect. “We protect fundamental rights, to protest, bear arms, to vote,” he said. “We are guardians of our democracy.” Stressing that officers shoulder this responsibility gladly, Love set the challenge for the remainder of the meeting as one of information – mapping the threat landscape to prepare law enforcement for situations they may not be anticipating.

After Love spoke, Hatch played the voicemails his own office received, escalating from a vague warning to a chilling direct threat of violent revolt, to establish that as in other states, election officials in Utah were vulnerable and needed protection.

Understanding each other’s operating environment

The Five Steps to Safer Elections suggests that showing the similarities and differences of their professional settings will help law enforcement and elections leaders reach consensus on solutions. Arbon and Ryan Cowley, Utah’s state election director, were tapped to join Hatch in delineating important aspects of their respective working environments.

Arbon described his office’s interactions with “first amendment auditors,” in the process drawing strong parallels with the election setting. These self-appointed constitutional activists engage in confrontations with law enforcement in order to test the boundaries of their right to free speech, seemingly to provoke difficult situations in which police can make mistakes, with the intention of creating grounds for a lawsuit.

He stressed these activists have rights and that law enforcement must tread carefully and treat them fairly, while maintaining confidence in their own mission. An important secondary message emerged from his narrative: First amendment auditors – and by analogy, election protesters – often misunderstand the procedures they’re angry about, engage in unnecessary confrontation, and misconstrue the motives and actions of the police or election workers they’re criticizing.

Arbon drew another parallel, emphasizing that like policing, election work is guided by statutes and written procedures that define and restrict the actions not only of election workers, but also of observers and protesters.

Senior Election Expert Tina Barton spoke with Weber County Clerk Auditor Ricky Hatch about what election officials can do in the weeks leading up to an election to partner with law enforcement.

With the audience primed to feel affinity, Cowley took the podium to assure police chiefs or sheriffs that elections deserve their trust. In a detailed overview of Utah election processes, he laid particular stress on aspects that help prevent cheating:

-

Pre-election “logic and accuracy” testing to show voting machines count correctly

-

Video surveillance at drop boxes

-

GPS tracking of ballots retrieved from boxes

-

Utah’s BallotTrax application, allowing voters to follow their ballot through the mail to receipt by the office, signature validation and inclusion in the tally

-

The right to observe

-

Paired staffing for ballot procedures (precluding unaccompanied access to secure materials)

-

Audits that confirm the accuracy of results

Cowley’s highlights emphasized the principles of cross-checking and openness to observation that help safeguard election integrity in Utah and across the country.

Agreeing on Expectations and Limitations to Security Support

The Five Steps to Safer Elections recommends that the group should discuss common election disturbances and preferred responses. By helping law enforcement recognize unique challenges of election work, a discussion of scenarios can help build a framework for consensus about the role of law enforcement during elections.

Chris Crockett, Chief Civil Deputy in the Weber County Attorney’s Office, and Brandan Quinney, the Assistant County Attorney assigned to the election office, led the discussion. They drew topics from CSSE’s reference guide for Utah law enforcement, which cites Utah’s election-related statutes.

Crockett spoke about rules of engagement – the circumstances under which law enforcement should or should not engage in and around an election site. “Making sure that things are happening appropriately in polling places, that ballots are counted, that falls to the election office,” he said. “You have training to know when there’s a threat to public safety. That’s the realm of law enforcement.”

Cautioning that law enforcement should wait for a request for assistance from election personnel unless they recognize an active threat, he nevertheless said, “Election workers can really use your experience and training in how to de-escalate situations that do arise.” Crockett directed attendees to a contact sheet in their packets as a source for names of central election office staff and senior workers at voting sites.

“Watch for the word interference as we go through the statutes,” Quinney, the liaison attorney, said, stressing the concept and its place in Utah’s election laws “Observing is fine. It’s when they engage that we get into these gray areas, and they may cross the line into interfering.”

Quinney led discussion of statutes from the pocket guide – electioneering, petitioning, observing and filming election procedures – and explained nuances. “I wouldn’t have a problem with filming ballot collection, but if they’re filming ballot opening, they would need to put the camera away,” he said.

An element of uncertainty for some attendees was whether police or the county sheriff had jurisdiction in election disputes. The question initially drew varying responses from the audience, but their answers converged. They would settle jurisdiction as in other arenas of law enforcement, working together and working it out.

“There’s going to be overlapping jurisdiction. We need communication. Communication with other law enforcement partners. Communication with the election office,” Quinney said, providing a synopsis of concerns about jurisdiction that could serve as a summary of the meeting itself.

Outcomes

The northern Utah experience proves that an election security meeting can galvanize election security cooperation. The meeting drew nearly 50 people, including election officials from five counties and law enforcement from six. The Lt. Governor’s Office, the Utah State Bureau of Investigation, the FBI, the US Department of Homeland Security and the Utah Association of Counties all sent representatives. The organizers believed strong attendance demonstrated recognition of the importance of the issue.

Hatch highlighted two outcomes from an elections perspective. First, simply opening lines of communication.

“There were police chiefs from my county that I hadn’t spoken with,” he said. “Two of them thanked me, saying the meeting was helpful.”

Hatch also felt the scenarios forced him to grapple with how he would respond in much greater detail than his previous thoughts on security.

Police chiefs echoed the clerk, saying the discussion of threat scenarios and the details of election law revealed a complex setting, and that hearing the threats against Hatch’s office proved their attention is needed.

A handful of significant moments during the meeting – nervous laughter and some attendees holding their heads in their hands while the threatening audio clips were played; the many police chiefs referencing the pages of the law enforcement pocket guide that addressed each scenario being discussed; and the multiple participants who offered ideas and responses to these scenarios – offered signs that the audience was engaging deeply with the topic.

The meeting served as a catalyst for regional consensus on election safety. Next steps will be local, as leaders in each county wrestle with the specifics of their security situation and how to prepare their personnel.

Partnering Successfully with Law Enforcement

If your jurisdiction and its counterpart law enforcement agency or elections office are interested in receiving support from the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections, click here. A committee member or supporting organization will get in touch with you.