March 21, 2023

Illinois’ Cyber Navigator Program

The case study and workbook are available for download:

How Illinois Developed the Nation’s First Statewide Elections Cybersecurity Program

Election modernization brought voter registration and other election services online. All digital systems have vulnerabilities. Sophisticated threat actors have exploited those vulnerabilities around the world. Election websites and public portals can be compromised by malicious hackers. Even offline or “air gapped” election equipment could be at risk. Ensuring secure, modern, and convenient service delivery requires election officials to stay in front of cybersecurity risks.

The Problem

On July 12, 2016, the Illinois State Board of Elections (the Board) detected unusual activity on the servers that hosted the Illinois voter registration database. Logs revealed malicious activity, later attributed to the Russians. The state quickly took the database offline and deployed new code to mitigate the vulnerabilities exploited by the cyberattack. By July 28, the system was back online and fully operational.

The personal information of more than 70,000 voters was compromised during the breach. Fortunately, no evidence emerged that any changes were made to any records or to the database itself.

The attack in Illinois revealed the need to enhance elections cybersecurity. It showed that breaching even a small jurisdiction’s security can lead to a successful cyberattack on a statewide system. But many local officials lacked the expertise, workforce levels, and resources to properly defend their systems, detect malicious activity, and recover business operations in the event of a successful attack.

The Solution

At the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center Conference (MS-ISAC) in April 2018, state and local election officials, state information security personnel, and state law enforcement hatched an idea to build a shared services program to protect election systems from cyberattacks. The “cyber navigators” concept was born.

The same month, the Elections Assistance Commission (EAC) awarded Illinois a $13 million Help America Vote Act (HAVA) security grant. Initially, the Board planned to distribute funds to counties based on voter registration counts. However, larger counties generally had a higher maturity level when it came to cybersecurity. In many cases, smaller localities needed more funds because targeted hacks might not discriminate between larger or smaller jurisdictions.

Local election officials from Cook County, Illinois led the charge to put HAVA funds to better use. They worked with legislators, other counties, and the Illinois State Board of Elections to agree on a solution.

The following month, the Illinois legislature acted, and Public Act 100-0623 was signed by the governor that July. It tasked the Board with using one-half of Illinois’ HAVA funds to create an expansive Cyber Navigator Program (CNP), the first of its kind in the nation. The CNP would support all 108 local Election Authorities to “defend against cyber breaches and detect and recover from cyber attacks.” Remaining funds would be allocated to local authorities on the condition that they participated in the CNP. Participation originally required the locals to complete the following:

-

Register with the Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing & Analysis Center (EI-ISAC),

-

Work with the CNP program manager to establish two-way data sharing,

-

Participate in annual security training, and

-

Participate in a CNP risk assessment.

In 2022 the legislature required counties to transition to a .gov domain and to receive persistent vulnerability scans of their public facing websites.

The Board held two public hearings to establish rules for the program to enhance both cybersecurity and operational security. Administrative rules were unanimously approved on August 24, 2018. They included three main pillars of the program: personnel, outreach, and infrastructure.

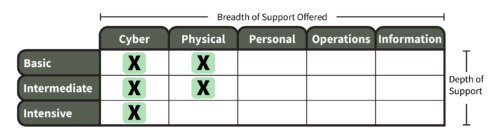

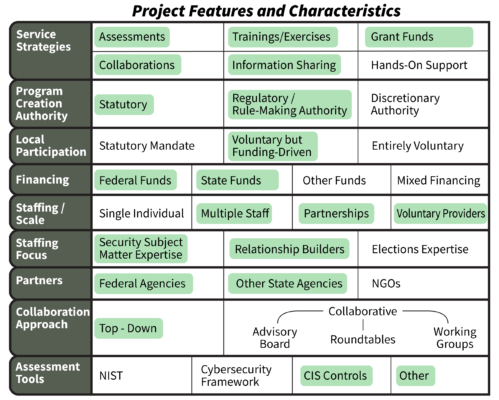

Project Features and Levels of Support

Illinois’ Approach

Personnel

At the heart of the CNP is a staff of eight Cyber Navigators (CNs) and two Cybersecurity Information Sharing Program Managers (CISPMs).

Cyber Navigators are cybersecurity specialists assigned to different geographic regions. They travel to election offices in their region to disseminate information and conduct risk assessments. They build trust and rapport with election authorities in order to evaluate the state’s cybersecurity landscape and to combat cybersecurity threats.

Cybersecurity Information Sharing Program Managers (CISPM) conduct workshops, table top exercises, and other outreach efforts, including a mandatory annual training. Program managers also provide risk assessments, incident responses, and serve as trusted advisors.

Voluntary participation

During public hearings before the program launched, counties expressed a desire to maintain local control over their voting systems. Amy Kelly, Cyber Navigator Program Manager at Illinois State Board of Elections, recalls there was some skepticism the State was acting like “big brother.”

“We worked our tails off,” Amy said of their efforts traveling to counties and speaking with local officials. The Board provided assurances that the program was intended to support counties with resources and guidance.

Participation in the CNP is voluntary. All 108, now 104 due to a consolidation, local election offices chose to onboard.

Holly Wilde-Tillman is the Clerk in rural Hancock County. “I wanted to set the stage for a good rapport with the State.” Her county lacked an in-house IT department. She knew that by partnering, they stood to improve their cybersecurity posture. “Even a small initiative” meant Hancock County was eligible for a $40,000 grant that allowed them to secure an IT vendor and improve their security.

In addition to risk assessments, counties receive continuing support and training to prevent phishing, malware, and other security breaches. Counties receive guides, checklists, and other resources to help combat election security threats.

Participating counties are eligible to receive HAVA security grant funds disbursed through the program. Illinois offered a base $10,000 grant to every county that volunteered to participate. Additional funds were available only to participating counties, allocated based on the voting age population for the Election Authority’s jurisdiction.

Risk assessments

A risk assessment tool was developed in-house following the CIS Security Controls. Adam Ford, Chief Information Security Officer for the State of Illinois recalls they started by using more detailed NIST assessments. “Clerks found it to be too many questions – intimidating to non-IT people.”

The more “conversational” language of their in-house assessment allowed for more productive, straightforward dialogue between State and local officials. For example, the Board found it effective to draw parallels between cybersecurity and basic concepts of home security. This also allowed them to discuss organizational security with counties, and not limit their conversations to network security.

Holly Wilde-Tillman is a “rule follower.” On her first experience with the assessment, she recalls “I wanted to get an A+.” She appreciated the opportunity to partner directly with her cybernavigator to identify areas for improvement and act on them. Because she works with IT contractors, there are frequently new people working with her. The assessment tool is integral to streamlining that work and making sure that every year they are able to “check more boxes off the list.”

The Board had previously explored cybersecurity controls put forth by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). However, it was important at the onset that counties could understand controls, and that they were written in plain English. Amy Kelly recalls the NIST controls “were a little too intense.” Pilot counties had a hard time working with them.

Partnerships

Election officials are not automatically cybersecurity experts. The Board understood the elections community would need the support and subject matter expertise from other agencies.

Early in the process, Board leadership recognized the importance of partnerships. Program Manager Amy Kelly recalls, “We really started to dig in and have robust conversations with other state agencies that we typically wouldn’t have partnered with to start the implementation and creation of this program.”

CNP operates under an interagency agreement between the Board and two state agencies.

-

The Department of Innovation and Technology (DoIT) establishes and manages the Illinois Century Network (ICN), which ensures the statewide voter registration database is securely accessed only from known, trustworthy IP addresses.

-

The Illinois State Police (ISP) develop and manage the fusion center, the outreach and awareness components of the program through which counties share information and report incidents.

The program also contracts with the Illinois National Guard, who can deploy resources during an emergency resulting from a cyber attack.

Outreach

Active sharing of cybersecurity information is central. The Board established an interagency agreement with the State Police’s Statewide Terrorism and Intelligence Center (STIC). Employing Cybersecurity Information Sharing Program Managers (CISPM), CNP compiles and shares election cybersecurity information for local authorities.

Other outreach efforts include:

-

An Incident Reporting Aid to identify common cyber and operational threats and provide election officials with specific, actionable steps to take in response to those threats.

-

A Cyber Incident Checklist to guide election officials how to investigate, remediate, and communicate when there is an identifiable election threat.

-

The Navigator News, which publishes appropriate program information to the public. This includes Navigator Spotlights, which introduce the public to the members of their community who are doing invaluable work.

-

Sharing information with the Federal Bureau of Investigations, Department of Homeland Security, Multi-State Information Sharing & Analysis Center, and the Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing & Analysis Center.

Costs and Funding

Startup costs were covered by federal Help America Vote Act security grants. Illinois received $13,232,290 in HAVA funds in 2018. The State was required to contribute a 5% match equal to $661,615 for a total budget of $13,893,905. Per Illinois law, half of the budget ($6,946,952.50) must be used to support all counties through the CNP.

One of the biggest initial expenses was deploying the ICN. The State estimated it would need $2 million and take 2 to 3 years to complete the infrastructure upgrades. It would take two years and an additional $2 million in personnel costs to complete risk assessments for all 108 counties. An additional $1.2 million would be retained by the State for consultants and equipment needed to maintain the program over a five-year period.

Other costs were associated with upgrading all offices to Windows 10, installing modern firewalls, and providing offsite digital storage.

During its first year of implementation, the State spent:

-

$1.1 million in cybernavigator personnel costs,

-

$724,000 in equipment, and

-

$62,000 in miscellaneous expenses such as hosting regional trainings and contracting with the National Guard.Impact

Impact

“We hear from (county) people I never thought would have buy-in and then we are able to push that information through to ISAC or CISA or the FBI,” says Amy Kelly. When the SolarWinds attack occurred, the elections cybersecurity network were all informed within minutes: no other sector in the State achieved that.

Through building direct relationships with local election officials, the program created a culture of willing and productive information sharing. For example, counties are quick to alert the program of potential phishing emails. “I know exactly who to call,” says Schuyler County Clerk Mindy Garrett. Trust in the program led to early awareness which improved the entire state’s cybersecurity posture.

The county response has been positive. Before 2016, Tazewell County Clerk John Ackerman recalls there being no significant cybersecurity program in his home county. Now he feels even more prepared than the private sector.

Ackerman highlights several program features having a direct impact on his office’s security posture.

-

The cybersecurity training his office receives “far exceeds what any of the other elected offices see” in other agencies.

-

Information sharing has been “outstanding” between the federal, state, and local partners. He feels very informed to both pass information to his local IT department and also educate his public.

-

Physical security audits have helped him and his sheriff look at their buildings with a fresh pair of eyes. “You look at this everyday, just like your home,” and without a formal assessment, counties might miss something.

-

The CNP has helped Ackerman prioritize and make informed decisions when it comes to allocating HAVA security grants.

Clerk Wilde-Tillman was eventually able to hire a part time in-house IT professional. “That person is in regular contact with my cybernavigator.” She also appreciates the continuing education and the direct communication. “If I get a suspicious email, I can send it directly to my cyber navigator.” Through the partnership, “we are growing and making ourselves better.”

Training and partnerships has led to an overall awareness of cybersecurity. Clerk Garrett, who oversees elections for her 4,800 voters in rural Schuyler County sees the benefit. Through her cybernavigator, she understands, “Other departments might not be getting the same training. Different agencies may share servers with elections.” It is important to her to share security information with other agencies.

The Illinois Board of Elections has not experienced a cybersecurity breach since the program’s launch. However, it is the State’s shift towards a culture of cybersecurity and open communications that has had the greatest impact.

Startup Timeline

The program launched with a commitment to timely action. CISPM outreach efforts began immediately in August 2018.

During the rest of 2018, the CNP onboarded cybernavigator personnel, began registering counties, and piloted several risk assessments. By the year’s end, they began performing risk assessments.

In early 2019, they continued with risk assessments and ran an annual training pilot. By midyear, they began conducting their first table top exercises.

Infrastructure Needs

CNP established the Illinois Century Network (ICN) to ensure secure connections between the State voter registration system and county end users. The ICN is professionally monitored and secured through an interagency partnership with the Department of Innovation and Technology.

Department of Innovation and Technology staff are responsible for maintaining network firewalls, installing security software, and monitoring the network’s use against intrusions. This ensures that all county election offices, no matter their size or cybersecurity maturity, operate on the same secure network.

The program upgraded the operating systems of entire offices, installed modern firewalls, deployed multi-factor authentication, and provided offsite digital storage backups. All these efforts combined dramatically improved Illinois’ ability to combat future cyber threats.

Obstacles and Advice

Back in 2017 and 2018, the very notion of a cyber navigator was loosely defined. Adam Ford recalls thinking about the KSAs needed to be a cyber navigator. “The kind of ideal person isn’t just wandering around Illinois looking for a job.” The initial obstacle was finding a person with the right set of technical and soft skills for the job.

However, they didn’t find it absolutely necessary to find someone extremely technically advanced. Adam Ford learned that someone mid-career, with an understanding of IT and a willingness to learn was as important to finding someone who could de-escalate difficult situations, build relationships, and add trust through their communication style.

Adam recalls an interview technique for potential team members. They would ask the candidate to explain a cyber security issue using a metaphor. This helped them see if they could explain something technical in plain language.

“If you’re not experimenting, you’re not keeping up.” – Adam Ford, Illinois Chief Information Security Officer

Program Manager Amy Kelly highlighted the tight timeline as a top challenge to implementation. The enacting legislation was signed mid-year in 2018. With a midterm election in months and a Presidential in 2020, “We had to hone in on and figure out what was most important to us.” Under short timeline, the CNP was pressed to hire cybersecurity managers and onboard 108 county election officials to a new program and new concept.

One of Illinois’s first hurdles was to get buy-in from all 108 local authorities. Illinois’s program is decentralized. Localities are not obligated to participate. The Board gained support by sending representatives to local meetings, county offices, and conferences to engage local election staff. Speakers were able to point to specific data breaches from 2016 to motivate election authorities to join the CNP.

The ICN is a long-term investment in election cybersecurity. To network and upgrade 108 counties would be a 2-3 year long effort. “It was massive,” recalls Kelly. Illinois is a mix of urban and rural areas, and sometimes establishing secure connectivity required the support of third party providers.

Scalability

In 2017, Illinois had already consolidated all information technology departments into one office under the governor. This was formalized by statute in 2018.

Program Manager Amy Kelly encourages interested jurisdictions not to get overwhelmed with the scope of this effort. “My number one piece of advice would be to remember that even small changes have a huge impact.” Even basic cybersecurity training can make a major difference in the awareness and maturity of a small jurisdiction.

Adam Ford’s sentiments resonate with Amy’s. “The most important thing with starting a program like this is no to overthink it. It doesn’t have to be over-planned. You’re starting where you’re at.”

Or using his penchant for metaphors, “It’s more like a recipe for soup than a recipe for cheesecake. It doesn’t have to be exactly right. (…) Would you let your house burn for five days before figuring it out?”

Other states considering such a program should consider a few items.

-

Relationships. Effective partnering with outside agencies and onboarding counties takes trust and coalition building. Those phone calls and meetings can begin now. The success of a statewide cybersecurity program is accelerated when state and local officials are on a first name basis.

-

Communications. Stakeholders must develop a clear communication plan to ensure the correct authorities are aware of emerging threats. States may need to develop strategic communications that articulate the real risks that their election officials face if they do not develop robust election security protections.

-

Funding. As of March 2022, states only spent 53% of the $800 million HAVA security grant funds. Election cybersecurity is a national priority. States considering a major capital or personnel investment may still have access to large amounts of federal funds. And remember, many program components such as regional training can be done at low costs.

Media and Recognitions

-

The federal Election Assistance Commission awarded the Board a 2020 Clearinghouse Award for Outstanding Innovation in Election Cybersecurity and Technology.

Clearinghouse awards are given to jurisdictions for best practices in election administration.